| I was born in Dublin in 1947. The third child of a family of twelve children—the next baby was born just a year later. By the time I was four and a half, there were three new babies younger than me. In 1951, at the age of four, I was sent to Goldenbridge Infants School. This was called: Low Babies. The Head nun, Sister Charles, caned any child who was late; one hit for each minute one was late. The children were panic-stricken while the minutes ticked by as they waited for her to arrive.My first public artwork was in 1952, when I was in High Babies. My teacher, Miss Scally, was kind, attentive and observant—she had spotted my talent. One day Miss Scally announced to the class with a clap of her hands: ‘Children, we have an artist in our class! Ciarán, would you like to go up to the blackboard and do a drawing for us?’ She pointed to the smaller blackboard on the wall, adjacent to the main one. I stood on a chair to reach it. (I was only five.) I immediately saw that I had a problem. I had never drawn on a black surface before. I chose a good stick of white chalk, and using its side, I filled in the profile skin of a man’s head. Then in order to make the whiter white of the eye, I used the hard point to create the illusion of an eye. I drew the man’s hair swept back, as was the style of most men in Ireland in the 50s. Miss Scally thanked me, and the class clapped. She left that drawing on the blackboard for the whole year. That was my first public exhibition—and an installation at that! Years later I realised how unusual it is for a five year old to draw directly from life.The following year I kept my head down and survived the harshness of Sister Brigid; plus five more brutal years at the Christian Brothers School: St Michael’s.During this period, I discovered the Holocaust from photographs that I saw in Webb’s bookshop on the Quays. Horrified and puzzled, I questioned my mother about the Holocaust; she said she didn’t believe it! When I questioned my uncle, he said that it was the fault of the Jews themselves. Feeling isolated, I now distrusted all adult authority, especially the Catholic Church and the Irish State. For the next three years, from twelve to fifteen, I went to the new vocational school on Emmet Road, Inchicore. I thrived on their curriculum, especially in art, design, mechanical drawing and draughtsmanship. I wanted to work in the field of art. But despite my pleas, I was sent to work as an apprentice fitter in CIE’s Coach Building unit.

Outraged, I was determined to leave Ireland and my job as an apprentice fitter. In order to get away, I needed a new identity. I spotted a boy, who was begging outside the Cinema. I gave him a shilling for his name, his mother’s name and his address. With this information, I walked into the Custom’s House, and for two and sixpence, I bought his Birth Certificate.In late November 1962, I arranged to be paid a day early: Thursday. So with my week’s wages, I took the Mail Boat from Dún Laoghaire to Holyhead. The following morning I arrived in Euston Station in London. Lost for a few days and penniless, I found an Army Recruiting Office. I joined the Royal Green Jackets. I was sent to a temporary Interment Camp, just outside Winchester. I trained there as a Rifleman from December 1962 – until my father found me! It was just two weeks before training completion and Marching Out. Discovering my true identity and the fact that I was underage, Col. Shouldice honourably discharged me. I arrived back in Dublin 29 March 1963, just sixteen and with no job. Back in Dublin, now using my own name, I entered the grand hallway of the National College of Art in Kildare Street for the first time. The magnificent staircase swept down to greet me, and atop, I saw the sculpture of the great Laocöon and His Sons. I felt I was home at last and understood. I was taken into the National College of Art on a Scholarship as a student of special talent. Being a year underage, I was given an extra year of Drawing from the Antique, which meant it was two years before I would draw from a live model. All of my problems appeared to be expressed in the Laocöon and His Sons; the young sons vying for the central authority of their father. From Lessing’s book and Virgil’s poem, I learned the story of the sculpture. I knew from then on that powerful formal invention could allow the viewer’s private inner experience find a space with the artwork that was free from storytelling and independent of arcane knowledge. The Laocöon—more than the other antiques that I drew from—gave me what would become, my measure. Asking myself: ‘Why was Ireland neutral during WW II?’ especially as I saw that the war was a clear fight for good against evil, I questioned why was there no art visualising and underpinning the principles of the new State—as there was for the Russian Revolution? I began to realise that the art that I loved so much and excelled at was the art of German Nazi Classicism. This gave me an urgent understanding of Giacometti’s art of the failure of representation. It was around this time that I saw the works of De Kooning, Pollock, Newman and Rothko in ‘Art USA’. I also saw the Johnson’s wax Collection at the Dublin Municipal Gallery. I began making my first non-representational paintings. I knew from the USA painters I had just seen that a fresh new art needed to appear here, if Ireland was to have confidence in itself. My response was to create Folded/Unfolded during 1969-72. |

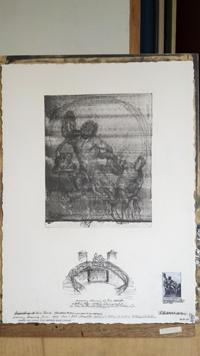

Laocöon and His Sons, Rhodes, Greece circa 10th Century BC  Memory drawing of the Laocöon made in NCAD, Kildare Street, 1963 graphite and wash  An early example of An early example of

the pictorial ground as Mother after La Madonna che allatta il figilo by Michelangelo

|

>